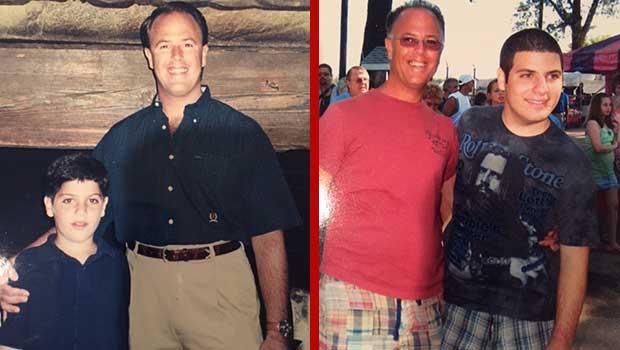

One Dad’s Wish for Father’s Day

As part of our ongoing Father’s Day series celebrating the unbreakable bond between dads and their children, Your Daily Dish is featuring amazing stories to highlight that special relationship. This is a personal essay about children with Autism and it was submitted by Robert Rosenfeld.

As dads everywhere prepare for Father’s Day, and families secure tee times and restaurant reservations, dads of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder often need something very different — something that is often overlooked.

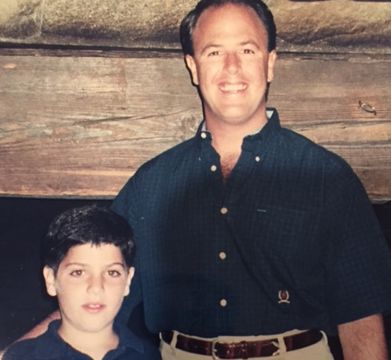

When our son, Bradley, was just over a year old, my wife Adrienne and I began to notice that he wasn’t responding to his name or to certain auditory stimuli. As he intently watched TV, we would call out to him, sometimes almost screaming at the back of his head, desperate to get his attention; he rarely turned his head. It was as if he was in another time zone — someplace very far away from us.

Other times, we sat in front of him on the floor, hoping to engage him. No matter how animated we were, he avoided eye contact — at all costs.

In his free time, he lined up his toys, over and over again. There was no sense of shared wonder or awe that comes with typical imaginary play. It was his little world, and we were on the outside looking in.

Parenting was so very different than it had been with our older daughter, Aly, who seemed to come into the world singing, dancing, and telling jokes. We knew something was wrong.

We explained our concerns to our pediatrician, who replied, “not to worry — my nephew did the same thing, and he’s a doctor today.”

However, the worry grew when we completed two rounds of intense hearing tests and Bradley began losing the few words he had in his vocabulary.

I uncovered a college textbook and turned to the index, which had one small paragraph about Autism (the book was from the 1970s, before incidence rates grew exponentially and people became more aware of the neurological disorder). As I read the description, I felt the combination of sadness and relief that parents of children with Autism know all too well.

It was devastating to see it all in black and white and realize that my son was, indeed, a “textbook case.”

The relief came from knowing that we could, at long last, get help. I showed the blurb to my wife, and we immediately got to work lining up early intervention services — a full-time job in and of itself.

Of course, like any parents, in spite of the countless hours of therapy and special instruction that became central to our days, we did what we could to create a life of “normalcy.” We brought Bradley on family vacations and to Broadway shows; we went to restaurants and socialized as much as possible. We were lucky in that sense — many families become prisoners in their own homes because of Autism. Oftentimes, friends stop extending invitations because a child is so disruptive, or parents know that their child simply cannot endure the sensory stimuli present at a restaurant or movie theater.

The truth, however, is that although our family did everything we could to maintain an “ordinary” family life, the knowledge of our son’s disability was always there, and extraordinarily painful. Well-intentioned family and friends tried to comfort us, making statements like “you are such great parents” or starting sentences with words like “at least Bradley can….” While we appreciated all of them for their unwavering kindness, they were overlooking one simple thing.

What we most needed from the people around us were open-ended questions about Bradley and his care; questions that would validate how different our journey was — questions that would allow us to truly share from our hearts.

We discovered the importance of this when we placed Bradley in full-time residential care at Anderson Center for Autism in Staatsburg, New York. He was 16, and by that point, our family was really suffering because of the 24/7 nature of his needs. We lived on Long Island at the time, and when we received news from Anderson that there was a bed available for Bradley, we once again experienced that painful blend of sadness and relief.

And while everyone around us was compassionate, my Aunt Bea knew exactly how to be helpful. Instead of making statements like, “you are so strong” or “at least Bradley will have a wonderful community”, which were the most commonly used phrases of other loved ones, she asked open-ended questions. “What was the admissions process like for you?”, “what will his living situation look like?”, “what was it like to bring him to Anderson Center for Autism?”, and “how is he doing with the transition?”

In asking questions, Aunt Bea was demonstrating true empathy. She gave us a safe harbor to share our fears, thoughts, and allowed us to solidify our feelings that Anderson Center for Autism was, indeed, the right place for Bradley. There was no judgment, there were no statements that diminished our feelings of melancholy (which stay with parents of most children with Autism throughout life). She genuinely wanted to know about Bradley’s new home and what this step was going to look like — both for him and for us. By asking questions, she was extending the kind of help that others had overlooked.

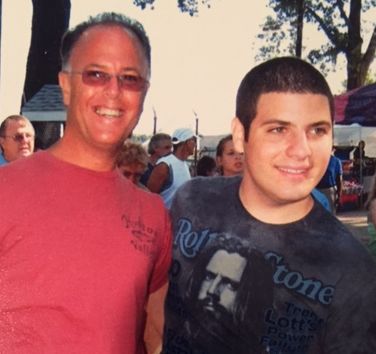

Today, we live in the beautiful Hudson River Valley region, having moved north from Long Island to live close enough to Bradley to share in his journey. He has done incredibly well at Anderson Center for Autism. With the loving care and expert methods delivered by their dedicated team of professionals, he has not only maximized his own independent living skills, but he has developed a network of peers and a community that has allowed him to enter a time zone and world that bring him real joy.

He has sold his work in local art shows, has trained in karate for years, and has won medals in the Special Olympics. Bradley consistently receives a message from his team at Anderson Center for Autism: that they believe in his potential and want nothing more than to give him the platform to shine. This has helped him develop strong self-esteem and has catapulted him to a happier, more self-assured space in the world. As for us, Anderson’s efforts have enabled us as a family to celebrate and be proud of Bradley for who he is; a true and everlasting gift!

We, too, have greater independence now, because of Anderson — and, in spite of the ongoing mourning that parents of children with Autism experience, we are confident and peaceful, knowing that we have given our son everything he needs by welcoming the opportunity to work with Anderson Center for Autism.

One of the most important lessons we learned through our journey is that Aunt Bea’s instinct to ask questions about Bradley was spot on. Rather than making general statements or avoiding the topic of Autism altogether, she catapulted this Dad to a greater experience of joy, even on the sadder days, by creating an environment designed for real sharing. I have been able to celebrate Bradley’s achievements with someone who has shown that she is genuinely interested in him.

As we approach Father’s Day, remember that each of us can take Aunt Bea’s example into our own lives. Dads everywhere are raising children with Autism. Many of them experience heartbreak every time they see their child’s peers learning to drive a car or heading off to prom — but there is also tremendous joy when they are given the chance to share milestones. Ask those Dads how their kids are doing and what their journey is like. Ask them how the teachers have been and what they most treasure about their children with Autism. Giving these Dads a chance to talk about their kids and their unique journeys as parents is the greatest gift any parent could want — on Father’s Day and every day.

Special thanks to Help a Reporter Out.