Advertisement

Family

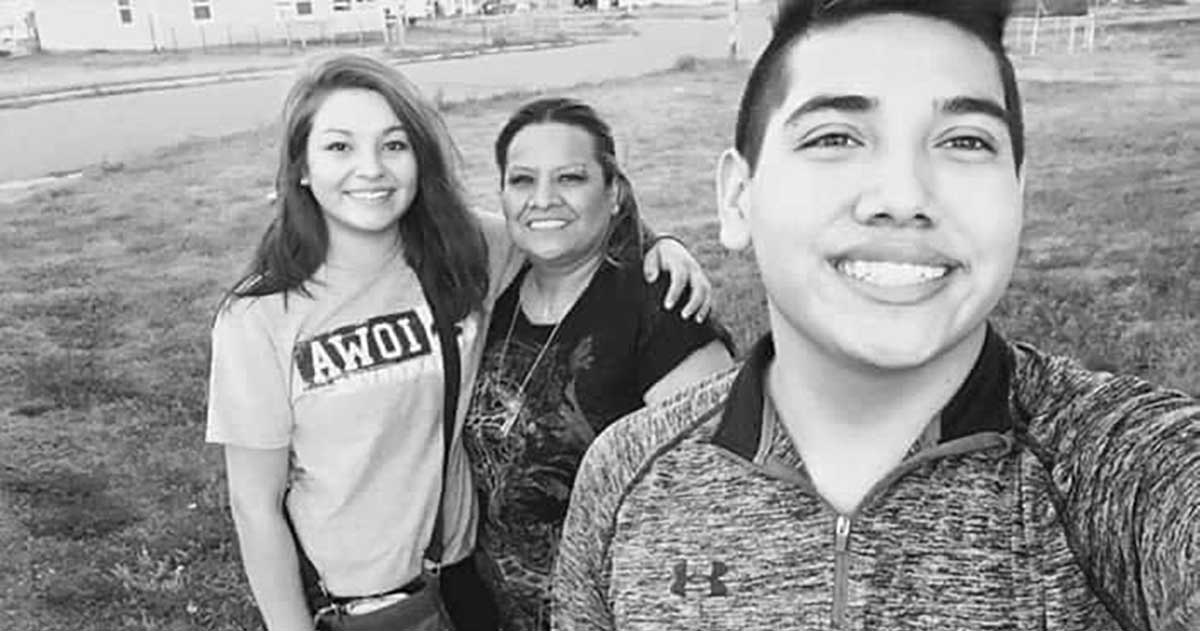

Mother Kicks Meth Addiction, Reclaims Custody of Son and Helps Others

By

Emily Rosenthal

5 min read

- # Bohdi LaPlante

- # Cheyenne River Reservation

- # Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

Advertisement - Continue reading below

In 2002, 3-year-old Bohdi LaPlante told his mother, “I didn’t know everyone had a friend named Crystal.”

A few weeks later, Bohdi’s aunt forced him to pack up his belongings and move in with her.

Bohdi and his extended family are members of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, which inhabits the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota. The toddler was correct: Eeveryone was talking about Crystal. However, Crystal was no friend to Bohdi’s family; his mother, Toni, later called Crystal “the evil, old devil.” Crystal is not a “she.” Crystal is the code name for the methamphetamine that is ravaging the lives of Toni and dozens of her fellow tribe members.

Toni Red Bear was first exposed to drugs on her reservation at age nine. Her parents regularly asked her to deliver packages to neighbors on the reservation. Toni was unaware of the contents in these packages.

“It was my family,” she said. “They asked me, so I would do it.”

She quickly learned that the packages contained a variety of drugs including marijuana, prescription pills, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Toni continued to abide by her family’s rules and frequently cleaned the house and watched neighbors’ children. When Toni turned 11 years old, her parents offered her an incentive for her housework: the opportunity to snort cocaine with older relatives after she finished her chores.

A phone call with Toni chronicled her downward spiral and also revealed a troubling Native American addiction crisis happening on reservations.

Getting high with family members became a daily occurrence for Toni. When she was 18 years old, Toni’s aunt offered her a hit of meth outside of a bar. She was instantly hooked.

“I got so addicted to it so quickly,” Toni remembers.

Toni cites a personal history of sexual abuse and abandonment issues for jumpstarting her meth addiction.

“It took me to a place of numbness,” she remembers. “It almost answered all of my ills — what I’d call them now is a soul pain. When I started doing meth, that’s kind of what killed that pain.”

The pain would not stop; nor would Toni’s meth-fueled nights out. Toni describes the drug as “ a cunning, baffling, lie.” She lost weight, and remembers feeling beautiful and invincible.

“In reality, I was slowly dying,” she acknowledged

Methamphetamine claimed three years of Toni’s life. She was sent to the emergency room six times after extreme hallucinations, unbearable symptoms of drug withdrawal, and a suicide attempt. Following her final visit to the hospital, Toni’s aunt took custody of Bohdi.

Toni hit a turning point in her life.

“I knew that I was going to die,” she remembers solemnly.

She checked herself into a rehabilitation center, regained custody of her son, and recently celebrated 13-and-a-half years of sobriety. Today, she works as a counselor for drug addicts. She describes life as a meth addict as a blurry vision of hell.

“It’s the old devil saying, ‘I can help you. I’ll fix you.’ And in a sense, all he’s doing is stealing your spirit so you’re no longer who you are,” she said.

Call it the devil or call it a chemical. Regardless, meth continues to appear in large amounts on Native American reservations.

The National Congress of American Indians reports that on reservation and in rural native communities, meth-abuse rates have been as high as 30 percent. Seventy-four percent of tribal police forces in South Dakota rank meth as the state’s greatest drug threat.

Methamphetamine is increasingly popular on tribal reservations, however scientists have found no evidence that Native Americans are genetically prone to drug addiction. Psychologists believe that addiction among Native Americans can be attributed to social isolation, generational trauma, and an overall loss of ethnic identity. According to the Treatment Episode Data Set Report, 2.5 percent of Americans admitted for addiction treatment are Native Americans, who comprise only 1 percent of the country’s population.

Due to the isolationist culture of Native Americans living on reservations, many Americans remain unaware of the drug epidemic occurring there. Fairfield University student Kerri Beine took a service trip to the Cheyenne River Reservation in August 2015. The student volunteers spent the first half of each day building houses and the second half running a summer camp for Lakota Tribe children. On the first day of camp, a boy named Xavier told Kerri that if he came home with dirt on his new sneakers, his father would burn him with a lit cigarette. Xavier was just one of the reservation children suffering from abuse at home.

Kerri remembers the prevalence of drugs on the Cheyenne River Reservation, the same place where Toni Red Bear grew up. The Fairfield student recalls from her service trip, “It was likely that the Lakota youth were children of alcohol or drug addicts. More often than not, we would drop the kids off after camp at their houses and watch them be welcomed home by their methed-out parents.”

The atmosphere of the reservation shocked Beine, however it is well-known among public-policy experts familiar with the culture.

A 2014 study by the Public Health Report investigated drug use among Native American students. It stated: “Prevalence rates for American Indian students were significantly higher than national rates for nearly all substances, especially for eighth graders. Given the high rates of substance use-related problems on reservations, such as academic failure, delinquency, violent criminal behavior, suicide, and alcohol-related mortality, the costs to members of this population and to society will continue to be much too high until a comprehensive understanding of the root causes of substance use are established.”

Despite these statistics, the federal government has defunded all grants that sustain Native American educational programs nationwide. In January 2017, the President Donald Trump’s administration announced that it would no longer finance the Eugene Natives Program, which largely integrated Native American ancestral history into its curriculum.

Erika, a high school senior who was enrolled in the Eugene Native Programs, advocated for the program, saying: “In school, native kids are often made fun of or put down for being native. The Natives Program provides them with the real story about Native Americans. They get to learn about their roots and all the positive aspects of their people’s ancestral heritage. Kids who feel good about themselves are less likely to get in trouble, which is not only a benefit to themselves and their families, but also to society as a whole.”

Native American leaders, including Toni Red Bear, have made efforts to combat the meth addiction on tribal lands. Last year, 24 people involved in methamphetamine sales and use were banished from the Cheyenne River Reservation. However drug-related crimes and deaths continue to rise in South Dakota. Cheyenne River Reservation residents are beginning to realize that “Crystal” is a cunning, baffling enemy —not a friend. She refuses to leave the reservation without a fight.

Please SHARE Toni’s story to help shed light on this troubling Native American addiction crisis.

Advertisement - Continue reading below